Chemical Warfare Against Appalachia

During the height of the opioid crisis, executives at Fortune 500 drug distributor AmerisourceBergen Corporation mocked West Virginians as “pillbillies” in internal emails, celebrating their callous disregard for the devastation their company helped fuel. In 2011, as AmerisourceBergen flooded West Virginia with 90 million doses of oxycodone and hydrocodone—enough for nearly 50 pills per resident over five years—employees circulated a cruel parody of The Beverly Hillbillies theme song. The lyrics jeered:

“Buy some pills. Take a load home. Y’all come back now, y’hear?”

The song depicted “a poor mountaineer, barely kept his habit fed,” ridiculing addiction while the state suffered skyrocketing overdoses, babies born dependent on drugs, and crippling economic costs. Among those sharing the email was Chris Zimmerman, who later became AmerisourceBergen’s chief compliance officer. The company’s vice president, lobbyists, and trade group representatives also participated in the exchange.

In another email, executive Cathy Marcum sneered at new drug regulations, writing: “One of the hillbilly’s [sic] must have learned how to read :-)”

The mockery coincided with the rise of the “Flamingo Express”—a pipeline of pills from corrupt clinics in Florida to Appalachia—and a death toll exceeding 420,000 Americans by 2018.

In Appalachia, 2022 overdose-related mortality rates for people ages 25–54 were 64 percent higher than the rest of the country. Yet in 2017, AmerisourceBergen settled West Virginia’s lawsuit for just $16 million, a tiny sum compared to the state’s $8.8 billion annual costs for dealing with the opioid crisis. (See There’s nothing funny about an addiction crisis)

The opioid epidemic didn’t ‘spread’ to the people of Appalachia—it was pumped into their veins by corporate elites who despised them. While West Virginians buried their loved ones, AmerisourceBergen executives laughed over emails, calling them ‘pillbillies.’ This wasn’t neglect. It was contempt, bottled and sold as medicine.

Bain Capital: Looting Pensions

We see another example of this same contempt in Bain Capital’s ruthless business model under Mitt Romney, which epitomizes elite exploitation, transforming worker pensions into private equity profits. Far from fostering job growth, Bain perfected leveraged buyouts (LBOs), saddling companies with unsustainable debt while extracting wealth through fees, dividends, and asset sales. Workers, who relied on decades of pension contributions, were left stranded when these hollowed-out firms collapsed.

The KB Toys case exemplifies this predatory strategy: Bain took over the company, loaded it with $85 million in debt, and paid itself a $121 million dividend, tripling its investment before KB’s bankruptcy cost 14,000 jobs and slashed retirees’ pensions by 60-80%. Bain’s $578 million profit came at the expense of workers, a pattern repeated across industries with no consequences for the financiers.

While executives and investors reaped windfalls, retirees and employees were reduced to economic casualties, their losses dismissed as inevitable market forces. The media’s glorification of private equity obscures this looting, normalizing wealth extraction from vulnerable workers.

Mitt Romney and Bain’s legacy isn’t just financial destruction—it’s the stark intentional betrayal of working-class trust, revealing a rigged system where elites profit from deliberate and premeditated ruin while evading accountability.

We could cite many other examples, but for anyone living in the West, the evidence of this contempt is all around: bands of violent feral criminals terrorizing the streets of our cities, the declining standard of living, the education system failing to pass on the most basic skills, and collapsing infrastructure are just a few of the most obvious symptoms of the assault on working people by an elite that despises their own citizens. Like the opioid crisis, these aren’t things that “just happened;” these are all results of plans drawn up in boardrooms, think tanks, and university faculty lounges.

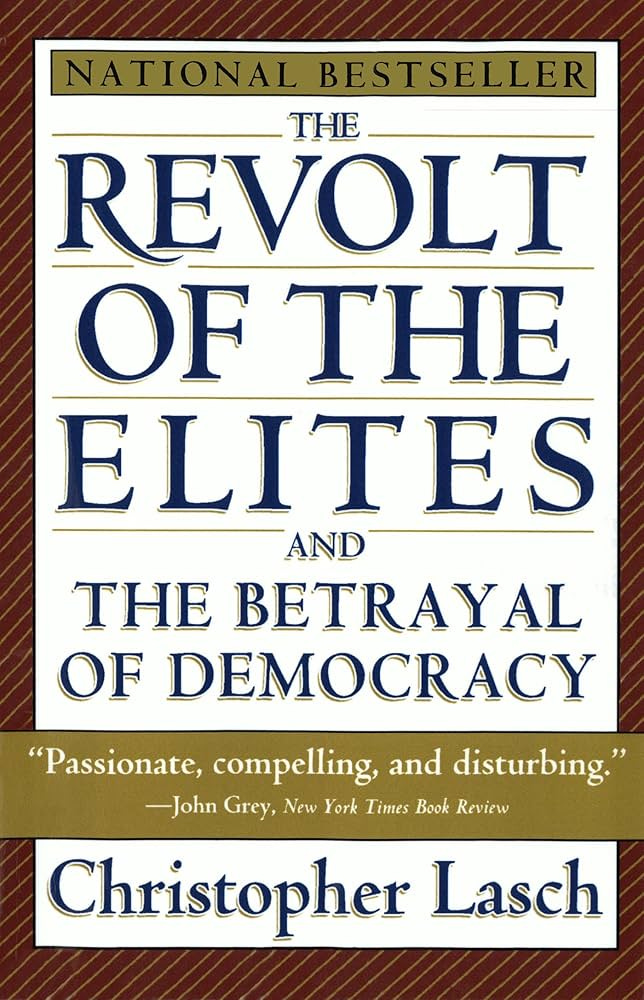

The Revolt of the Elites

Christopher Lasch identified this phenomenon in his 1995 The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. Where José Ortega y Gasset had warned of the "revolt of the masses," Lasch identified our era's core crisis: "The new danger is the revolt of elites," he wrote, "who no longer believe in the society they nominally lead."

This foundational insight captures the essence of Lasch's critique - that democracy's gravest threat comes not from below, but from an aloof professional class that has severed its ties to common life while retaining control of society's key institutions.

Lasch's portrait of this new aristocracy is brutal and unsparing. He describes a professional-managerial elite that has "withdrawn from common life" into enclaves of privilege, exhibiting what he calls "a curious combination of sophistication and spiritual poverty" - worldly in their tastes yet provincial in their understanding of human needs. Unlike traditional elites who at least nominally accepted obligations to their communities, today's ruling class has "lost the capacity for loyalty to anything outside themselves."

The depth of Lasch's critique becomes clear in his examination of elite ideology. He observes that modern elites justify their position through what amounts to a secular theology of merit: "The new elites' claim to power rests on the assertion of meritocratic achievement," Lasch writes, "but this masks what is essentially a new hereditary principle." Here he anticipates later work like Michael Sandel's *The Tyranny of Merit*, showing how credentialism creates the illusion of openness while actually reinforcing class boundaries. The result is what Lasch terms "a parody of democracy," where "equality of opportunity has become the ideology of a new aristocracy."

This analysis finds particular force in Lasch's examination of elite multiculturalism. Unlike conservative critics, Lasch approaches the issue from the left, seeing in elite diversity rhetoric not genuine pluralism but what he calls "the spiritual discipline against resentment" - a way for the privileged to congratulate themselves while avoiding substantive change.

"The multiculturalism of the elites," he notes, "consists of sampling exotic cuisines and collecting ethnic art, while carefully avoiding any real engagement with the cultures they claim to celebrate." This performative cosmopolitanism allows elites to "imagine themselves citizens of the world while remaining oblivious to the collapse of communities in their own backyard."

Lasch reserves particular contempt for what he calls the "therapeutic worldview" of the professional class - their tendency to recast political and economic problems as matters of personal adjustment. "Having given up on the possibility of meaningful change," he argues, "the new elites can only offer the oppressed various forms of psychotherapy." This mindset explains everything from corporate mindfulness programs to the transformation of activism into identity performance and sanctioned virtue signaling.

When placed in dialogue with classical elite theory, Lasch's analysis raises questions about whether democracy, as commonly understood, is even possible. The fundamental insight of thinkers like Gaetano Mosca, Vilfredo Pareto, and Robert Michels is that all societies, regardless of their formal political systems, are ultimately ruled by elites. Mosca's "iron law of oligarchy" holds that "in all societies...two classes of people appear - a class that rules and a class that is ruled." This is not a normative claim but an empirical observation about how power actually operates. (for the definitive introduction to elite theory, see Neema Parvini’s The Populist Delusion)

Pareto's theory of elite circulation adds a crucial dimension: elites maintain power not through brute force but by developing narratives that legitimize their rule. In medieval Europe, it was divine right; today, it is meritocratic achievement and technical expertise. As Lasch observes, today's elites justify their dominance through "the pretense that society can be ruled by experts," creating what amounts to a secular priesthood of credentialed professionals. What the regime media calls the “international rules-based order” is precisely this.

Robert Michels' contribution was perhaps most devastating to democratic illusions. Studying socialist parties in early 20th-century Europe, he concluded that even organizations formally committed to equality inevitably develop oligarchic structures. "Who says organization, says oligarchy," he declared. This insight applies with particular force to our current moment, where progressive institutions preaching egalitarianism often exhibit the most rigid hierarchies, and where governments arrest private citizens for social media posts and prosecute and arrest popular political candidates to preserve “our democracy.”

These theories collectively suggest that democracy may be structurally impossible in the sense of meaningful popular self-rule. Electoral competition simply becomes a mechanism for rotating which elite faction holds power, while the fundamental distribution of authority remains unchanged. Lasch himself approaches this conclusion when he notes that "the question is not whether society will be run by an elite, but what kind of elite it will be."

Lasch's work ultimately ends in a dead end for those committed to democracy. His critique of elite secession is so thorough that it undermines faith in democratic solutions, yet his vision remains rooted in democratic ideals.

Gurdjieff, Democracy, and the Elite

Like Lasch, GI Gurdjieff, in his epic All & Everything, was highly critical of the elites, referring to them as “power-possessing beings” who assigned others into classes and castes to free themselves from labor and allow unchecked indulgence of their appetites.

Unlike Lasch, Mr. Gurdjieff was no fan of democracy; one of his core observations is that most men suffer from ‘credulity’ and ‘suggestibility’ to such an extent as to make self-governance or democracy ridiculously impossible. Democracy, the political myth of a corrupt and degenerate elite, is an essential part of the problem and is incapable of offering solutions to our crisis.

Returning to our question: If elite rule is inevitable, how can we cultivate elites worthy of their station? More than political ideology, economics, or other burning questions, this is the core challenge of our time. As the West collapses, key institutions and infrastructure fail, and our cities are reduced to violent, filthy hellholes, restoration and renormalization will only happen as a result of the cultivation of an elite trained and oriented towards proper civilizational ends. What is preserved through the collapse and what emerges from its ruins will be determined by the quality of leadership and organization we form now.

GI Gurdjieff devotes four chapters of his epic Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson to outlining his understanding of how this elite leadership could be formed and how they could have a restorative influence on what he calls “the abnormal being conditions.” Conspicuously ignored by contemporary New Age ‘Fourth Way’ doyens, these chapters, devoted to the work of Ashiata Shiemash and his Order, outline the central mission of Gurdjieff and his Work. In coming posts, we’ll break down these chapters and take a look at what we must do today. According to Mr. Gurdjieff, everything depends on this.

Read more:

Shopping with Ashiata Shiemash