Yesterday evening, I was at the supermarket when something profoundly normal happened.

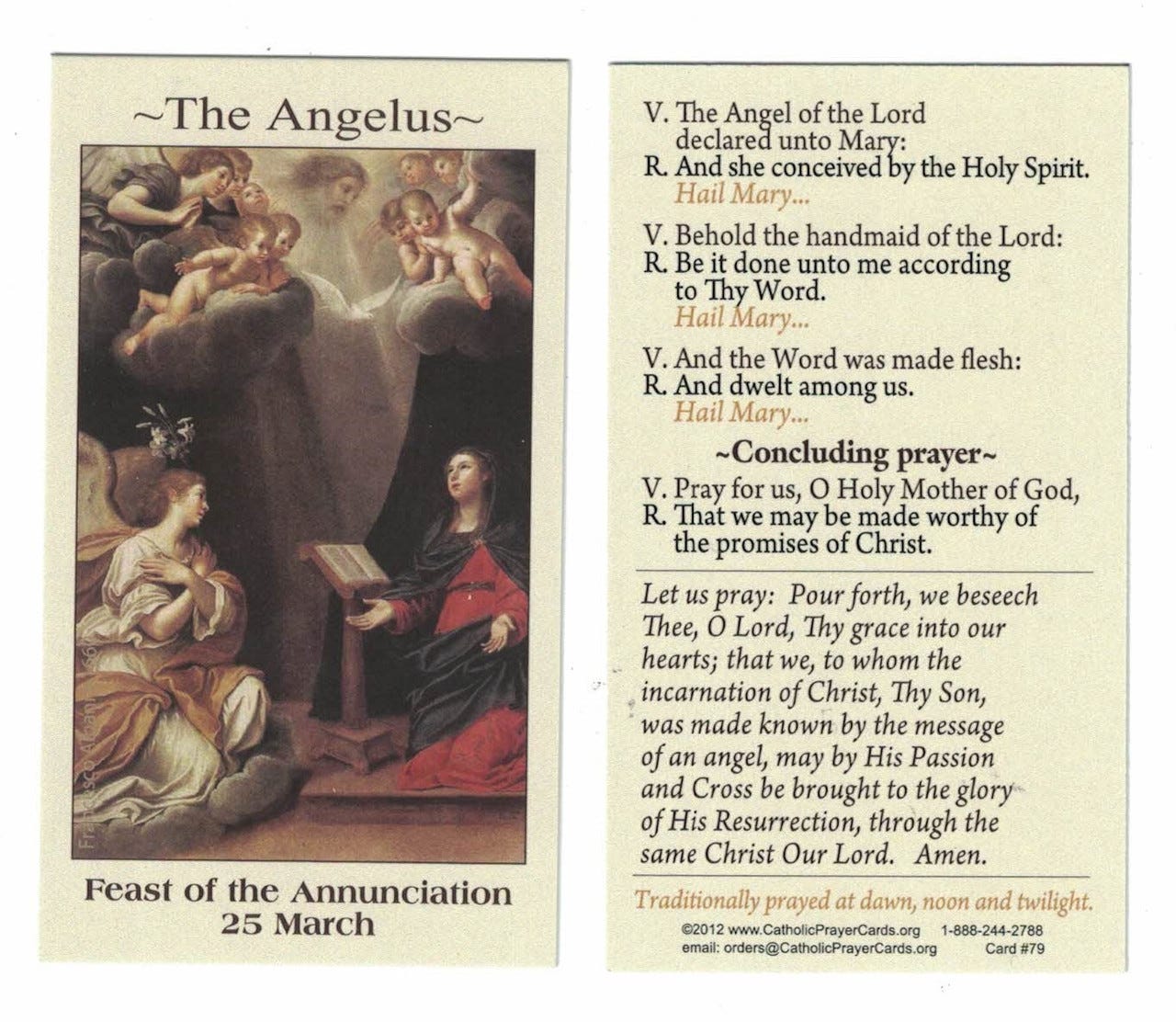

At 6:00 p.m., a voice came over the store’s public address system to pray the Angelus, a Catholic devotion traditionally recited three times a day. Everyone stopped what they were doing. Some bowed their heads, while others joined in the prayer. At its conclusion, many made the sign of the cross before resuming their shopping.

Now, try to imagine such a scene in a supermarket in the U.S. or Western Europe. The mockery, the outrage, the inevitable Antifa protests, and the breathless Rachel Maddow segment on “the growing threat of right-wing Catholicism” (somehow tied to the Russians, of course) would dominate the discourse. Yet here in the Philippines, this moment passed without controversy—a quiet reminder of a society that still retains what G.I. Gurdjieff called patriarchality and piety.

You won’t hear these terms mentioned by boomer “Fourth Way” enthusiasts, nor will they discuss related concepts like genuine being-duty, abnormal being-conditions, or paying for one’s arising. And for good reason: they’ve abandoned Gurdjieff’s worldview in favor of one driven by indulgence, titillation, and the rejection of fundamental obligations. But for Gurdjieff, patriarchality and piety were essential to maintaining a normal society and developing candidates capable of assisting in the work of Ashiata Shiemash.

You may have never heard of Ashiata Shiemash, even if you’ve spent years in Gurdjieff-adjacent circles. His story is conspicuously absent from groups whose worldviews are shaped not by the Work, but by humanistic psychology, the sexual revolution, and New Age self-calming. Yet for Gurdjieff, the mission of Ashiata Shiemash was central to his own purpose. As he stated plainly in the Paris Meetings of 1943:

“A collective existence is only possible through one system: that of Mr. Ashiata Shiemash. Right now, our only concern is the development of candidates to become future followers of Ashiata Shiemash. Later on we will choose among them. Do you understand?”

Our only concern. It’s odd then, that it’s almost never mentioned.

To summarize Gurdjieff’s account (found in All and Everything, beginning in Chapter 25), Ashiata Shiemash was a Messenger from Above sent to address the abnormal conditions of human existence. His mission was to restore humanity to a state of “normal being-existence,” characterized by alignment with objective reality and free from the distortions of egoism, mechanical habits, and destructive external influences that Gurdjieff calls the “abnormal being conditions.” Central to his method was the restoration of Objective Conscience within individuals.

Ashiata began with an Order of initiates, instructing them in his method before sending them out to teach others. Their achievements were so profound that, within a decade, wars ceased, corrupt institutions dissolved, and the entire social order realigned toward this higher aim. Yet these reforms were ultimately undone by Letrohamsanin, a political activist, and his acolytes in academia—whom Gurdjieff called “learned beings of new formation.” Their maleficent activities destroyed the remnants of Ashiata Shiemash’s work, as detailed in Chapter 28, The Chief Culprit in the Destruction of All the Very Saintly Labors of Ashiata Shiemash.

If Gurdjieff’s “only concern” was the development of future followers of Ashiata Shiemash, then this must also be the standard by which we evaluate any organization or teaching claiming to align with his ideas. Is the aspiration to develop such candidates central? If so, it is promising. If not—if the focus is on self-fulfillment, inner peace, or spiritual titillation—then it is something else entirely.

So what does all this have to do with the Angelus in the supermarket?

In an earlier post (The Lynching of Harrison Butker), I discussed Gurdjieff’s emphasis on patriarchality and piety as necessary for individuals to “be at least a little as it is becoming to three-centered beings to be…”

These being-impulses are foundational for even a somewhat normal society and for the development of humans capable of entering the Work. They create the conditions for what Gurdjieff called a “struggle between yes and no,” orienting individuals toward purposes higher than self-gratification and providing the data necessary for developing Objective Conscience.

The abandonment of these impulses, however, leads to what Gurdjieff described as the triumph of the “evil-God” within—a force that drives individuals to seek “a complete absence of the need for being-effort and for every essence-anxiety of whatever kind it may be.”

Western modernity, under the banner of “progressivism,” has waged a decades-long assault on patriarchality and piety. These values are now almost entirely absent in much of the West, surviving only in remote rural areas—which is precisely why elites harbor such contempt for these regions. The same diabolical forces are at work in the Philippines, where USAID-funded projects target traditional marriage and family structures, just as they have worldwide.

Boomer New Age “Fourth Way” enthusiasts often claim that the Work has nothing to do with politics, even as they champion the progressive ideologies that would make the Work impossible. But for serious students of Gurdjieff’s teachings—those who share his aspiration to develop “candidates to become future followers of Ashiata Shiemash”—the preservation of patriarchality and piety is not a political issue but a sacred duty. These being-impulses are the bedrock upon which the possibility of the Work rests. Without them, the path to Objective Conscience is closed, and the mission of Ashiata Shiemash remains out of reach.

In the end, the Angelus in the supermarket is more than a quaint cultural practice. It is a small but vital act of resistance against the dark forces that seek to destroy the very conditions necessary for human development. For those who understand the stakes, the task is clear: to defend and nurture these traditions, not out of nostalgia, but because they preserve being impulses that are essential to the Work and to the future of humanity itself.

In a world increasingly defined by the assault on good being habits, the erosion of duty, and the pursuit of self-gratification, the simple act of pausing to pray the Angelus in a Filipino supermarket stands as a quiet but profound reminder of the essential power of patriarchality and piety. These being-impulses, as Gurdjieff emphasized, are not superstitious relics of a bygone era but essential foundations for a society capable of nurturing individuals who can aspire to something higher than their own desires. Without them, the development of Objective Conscience—the very heart of Ashiata Shiemash’s mission—becomes impossible.

As we witness the relentless assault on these values in the West and beyond, it falls to those who understand their significance to resist the tide of modernity’s nihilism. For in preserving these traditions, we can work to lay the groundwork for a future where initiation might continue to be a possibility, and candidates can once again take up the work of Ashiata Shiemash.