England - From Sacred Authority to Mercantile Tyranny

GI Gurdjieff, Tradition, and the 'Glorious Revolution'

History, they say, is written by the victors. This means that the history we learned in school and from the media was written by the ‘power possessing beings’ described by GI Gurdjieff in his epic All & Everything. This fabricated history is an advertising campaign or political myth used to justify their crimes and to legitimize their power and is just as fraudulent as a typical CNN broadcast.

Mr. Gurdjieff emphasized that the central aim of his project was the normalization of being conditions on planet Earth, using the model of Ashiata Shiemash. Despite what you might have been told, the Work is fundamentally political - just not in the way you’ve been trained to think about politics. If we hope to effect lasting change using this model, it’s essential to have an accurate idea of where we are and the forces that got us here.

To that end, this is the first in a series of posts attempting to examine key historical periods and transitions from the viewpoint of the Gurdjieff Work and its aims, rather than through the ideological lens of the contemporary ‘learned beings of new formation.’

The history of England from the Tudor period through the Glorious Revolution represents much more than a series of political transformations. It marks a significant and systematic inversion of traditional social order that changed the very nature of Western civilization. To understand the magnitude of this catastrophic transformation, we must first understand what was lost: a social order arranged to facilitate humanity's spiritual development and maintain harmony between divine and temporal authority. Not a perfect system, but a system organized on sound principles toward a legitimate aim.

In the traditional understanding, as preserved in various esoteric traditions, human society naturally arranges itself into four distinct orders, each with its own function in maintaining stability, material prosperity, and spiritual development. This "Four-Fold Social Order" consists of the sacred order (Brahmins), the warrior-nobles (Kshatriyas), the merchants and craftsmen (Vaisyas), and the laborers (Sudras). When properly arranged, these orders work in harmony, with each fulfilling its proper role under the guidance of genuine spiritual authority. This allows the entire civilization to participate as a node in the network of cosmic reciprocal maintenance, while facilitating the appropriate role for individuals, based on their potential and degree of development.

It is crucial here to understand how this natural arrangement differs from what Gurdjieff describes in All and Everything as the artificial "division into castes and classes" that emerged after the loss of genuine tradition. As he explains, these artificial divisions were established when "the power-possessing beings" began to divide beings "into various castes and classes, and these differentiations became fixed and transmitted by heredity from generation to generation."

This division, rather than serving the harmonious functioning of the whole of society, was implemented so that a predator class could cease working and indulge their depraved desires, while those of ‘lower’ status are seen as prey or property.

Gurdjieff describes in detail how these artificial divisions operate. The power-possessing beings first create what he calls "various names for castes and classes," then establish "all kinds of 'rights' and 'non-rights,'" and finally institute "various restrictions and limitations." These divisions are maintained through what he terms "the maleficent idea of 'taking-revenge-on-the-beings-of-other-castes-and-classes'" - essentially, keeping different groups in conflict with each other to prevent them from recognizing their common exploitation.

This artificial stratification served what Gurdjieff calls "the hasnamussian aims of the power-possessing beings," creating a system where "the beings of one caste or class could never mix with beings belonging to other castes and classes." The purpose was to ensure that "these latter would not develop in themselves the divine property of genuine conscience" and thus remain easily exploitable.

Unlike the traditional Four-Fold Order, which existed to facilitate spiritual transformation and maintain cosmic harmony, these artificial divisions existed solely to maintain the power of what Gurdjieff terms "the parasitic beings" who "do not actualize being-efforts at all" but live off the labor and suffering of others.

This mechanism became particularly clear in post-Reformation England, where the new financial elite used both an emerging Protestant ideology and newly-created economic theories to justify their privileged position. As Gurdjieff puts it, they created "various outer coverings, or, as they say there, 'colorful outer signs'" to distinguish themselves from others, while simultaneously establishing "regulations and prohibitions" to prevent genuine social mobility or spiritual development.

In All and Everything, Gurdjieff describes how the civilization of Atlantis was organized precisely for the transformation of energies and the spiritual development of its people. He writes that their society was arranged so that "their being-existence might flow more or less tolerably in the process of their gradual self-perfection." This wasn't merely a political arrangement but a complete system for human transformation that also met the needs of the cosmic system of reciprocal maintenance.

The key to maintaining this order, as René Guénon explains in Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power, lies in the proper relationship between spiritual and temporal authority. The spiritual authority must remain superior to and independent of temporal power, while simultaneously legitimizing it. This creates a harmonious relationship where temporal power serves its proper function without attempting to usurp or replace spiritual authority.

Medieval England, particularly under the reforms of St. Dunstan in the 10th century, provides us with a clear example of this traditional ordering. As Archbishop of Canterbury, St. Dunstan established a system where the spiritual authority of the Church, represented by the Archbishop, legitimized temporal power through the coronation ceremony. This wasn't merely symbolic - it represented a metaphysical reality where temporal power derived its legitimate authority from spiritual power, which in turn derived its authority from divine sources.

Dunstan's reforms went far beyond clarifying the relationship between Church and Crown. He reformed the monasteries, transforming them into genuine centers of spiritual development - similar to what Gurdjieff describes in his account of Ashiata Shiemash's reforms, which began with his work with esoteric brotherhoods. Under St. Dunstan’s instruction, these monasteries served as centers of learning, preserving both outer knowledge and inner traditions of transformation. They maintained libraries, educated scholars, and most importantly, preserved the practices and understanding necessary for genuine spiritual development.

The society Dunstan helped establish represented the Four-Fold Order in proper arrangement:

- The sacred order (Brahmin), represented by the Church and particularly the monastic orders, maintained spiritual knowledge and authority.

- The warrior-nobles (Kshatriya), led by the divinely-appointed king, maintained order and justice.

- The craftsmen and merchants (Vaisya) created and distributed material goods

- The laborers (Sudra) provided the necessary physical work to maintain society

Each order had its proper place and function, working together in a harmonious whole. The monasteries themselves provided a concentrated model of this proper ordering, where prayer, work, and study were integrated into a coherent way of life directed toward higher aims.

This arrangement wasn't perfect - nothing at this level can be - but it provided the conditions necessary for both social stability and spiritual transformation. More importantly, it maintained the crucial distinction between spiritual and temporal authority while preserving their proper relationship.

However, this order contained within itself the seeds of its own transformation. As Guénon points out, the very success of such a system in creating stability and prosperity can lead to a gradual forgetting of its higher purposes. The contemplative class can become corrupted by worldly concerns, the warrior class can become more interested in luxury than duty, and the merchant class can begin to see profit as an end in itself rather than a means to support society's higher aims.

The Norman invasion of 1066 facilitated this corruption, as the usurper king replaced bishops, abbots, and other spiritual authorities with his cronies and supporters.

By the time of the Tudor period, these corrupting influences had been at work for centuries. The Church had become increasingly involved in temporal matters, accumulating wealth and political power. Many monasteries had strayed from their original purpose, becoming wealthy landowners more concerned with revenue than spiritual development. The nobility had largely forgotten its true function as a warrior class dedicated to justice and order. These conditions set the stage for the great inversion that would begin with Henry VIII.

The First Inversion: Henry VIII and the Subordination of Spiritual Authority

The actions of Henry VIII represent the first and perhaps most fundamental inversion of traditional order in English history. While often portrayed merely as a political conflict over marriage, divorce, and succession, the English Reformation constituted a metaphysical revolution that inverted the proper relationship between spiritual and temporal authority.

The Act of Supremacy in 1534 declared the king to be the "Supreme Head of the Church of England," effectively subordinating spiritual authority to temporal power. This was not merely an administrative change - it represented a complete inversion of the traditional order established by St. Dunstan. Instead of spiritual authority legitimizing temporal power through the coronation ceremony, temporal power now claimed the right to legitimize itself and control spiritual matters.

As Guénon points out in "Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power," this type of inversion is catastrophic because it destroys the very basis of legitimate authority. When temporal power attempts to usurp spiritual authority, it loses its own legitimacy in the process. The king, whose authority traditionally derived from divine sanction through spiritual authority, now claimed divine sanction directly - a claim that could never be truly legitimate within the traditional understanding.

The dissolution of the monasteries that followed was not merely a grab for wealth and land, though it certainly served that purpose. From the perspective of Gurdjieff's understanding, it represented the systematic destruction of centers for human transformation. The monasteries, despite their corruption, still preserved ancient methods for the development of consciousness and being. Their dissolution scattered these traditions and destroyed the physical spaces where such work had been carried out for centuries.

This destruction had profound implications for the Four-Fold Social Order:

The Brahmin function - maintaining spiritual knowledge and authority - was replaced by state functionaries in clerical garb. The new Church of England bishops derived their authority not from spiritual succession but from royal appointment. This wasn't merely a change in personnel; it represented the replacement of genuine spiritual authority with a political function.

The Kshatriya function was corrupted at its source. The king, by claiming spiritual authority, abandoned his proper role as temporal ruler under spiritual guidance. This created a fundamental contradiction: a temporal power claiming its own spiritual authority. As Guénon explains, this inevitably leads to the degradation of spiritual and temporal authority.

The Vaisya class began its ascent to greater power during this period, as the dissolution of the monasteries created opportunities for merchants and lesser nobility to acquire land and wealth. Without the guardrails of tradition and legitimate authority, the Vaisya tendency towards greed and accumulation of wealth at all costs was left unchecked. This began a gradual shift in the balance of power that would accelerate over the following centuries.

The Sudra class, the common people, lost access to the spiritual resources and guidance once provided by the monasteries. While many of these monasteries had indeed become corrupt, they still served as centers of education, healthcare, and spiritual guidance for the common people. The lives of the common people were given profound and potentially transformative meaning by the rich traditional cycle of feasts, fasts, and commemorations. Their destruction left a void that would never be properly filled.

Henry's reformation established several key patterns that would characterize subsequent developments in English society:

1. The subordination of spiritual matters to political expediency

2. The use of state power to enforce religious conformity

3. The transformation of spiritual institutions into instruments of state control

4. The elevation of economic considerations over spiritual principles

These changes intensified the conditions for what Gurdjieff calls the "abnormal conditions of ordinary being-existence." With genuine spiritual authority removed and temporal power corrupted by its attempt to usurp spiritual functions, society began to orient itself increasingly toward purely material aims.

The Tudor-Stuart Period: Acceleration of Decay

The reign of Elizabeth I accelerated these transformations, though in a subtler and more sophisticated manner than her father's direct assault on spiritual authority. Under Elizabeth, England saw the rise of the merchant adventurer system and the beginnings of what would become British commercial supremacy. This period perfectly illustrates what Guénon describes as the gradual usurpation of power by the merchant class.

The establishment of the East India Company in 1600 marked a crucial development. This wasn't merely a commercial enterprise - it represented a new kind of power structure where the Vaisya class (merchants) began to take on functions traditionally reserved for the Kshatriya class (warrior-nobles). The company maintained its own armies, conducted diplomacy, and governed territories - all functions properly belonging to the warrior-noble class under traditional order.

Elizabeth's reign also saw the effective legalization of usury through various legal fictions. This development cannot be understood merely in economic terms. As Guénon points out, the prohibition of usury in traditional societies wasn't simply a moral or economic regulation - it reflected a deeper understanding of the proper nature of money as a medium of exchange rather than a source of power in itself. The acceptance of usury represented a fundamental shift in how society understood wealth and its proper role.

The early Stuart period brought these contradictions into sharp relief. James I's doctrine of divine right of kings can be understood as an attempt to compensate for the loss of genuine spiritual authority. Unable to claim legitimate authority through proper spiritual channels (which had been destroyed), the monarchy attempted to claim direct divine sanction. This claim, as Guénon explains, was inherently illegitimate because it bypassed the necessary mediating role of genuine spiritual authority. It is in this context that we can understand Gurdjieff’s criticism of hereditary monarchy; any system without conscious spiritual influence is a dead end.

During this period, we see the emergence of what Gurdjieff calls "wrong crystallization" in social functions. The outward forms of traditional order remained, but their inner meaning and proper relationships were increasingly lost:

- The Church of England maintained the forms of spiritual authority while functioning as a department of state.

- The nobility retained its titles and privileges while increasingly abandoning its traditional responsibilities.

- The merchants began to take on quasi-governmental functions while remaining oriented toward profit.

- The common people were increasingly cut off from traditional sources of spiritual knowledge and guidance.

This period also saw the rise of what Gurdjieff terms "phantasmagoria" - elaborate justifications for arrangements that contradicted natural law. The theological arguments for royal absolutism, the economic justifications for usury, and the religious persecution of both Catholics and radical Protestants all represent attempts to rationalize arrangements that deviated from traditional order.

The growing power of London's merchant class during this period manifested in increasingly direct political influence. The monetary demands of the crown led to greater dependence on merchant bankers, while Parliament - especially the House of Commons - became increasingly dominated by commercial interests. This represents what the Four-Fold Social Order article describes as an inversion where the Vaisya class begins to dominate both the Kshatriya and what remained of the Brahmin functions.

By the time of Charles I, these contradictions had become acute. The monarchy claimed absolute divine right while being increasingly dependent on merchant financing. The established church claimed spiritual authority while being subordinate to temporal power. The merchants exercised increasing political power while maintaining the fiction of merely engaging in commerce. These contradictions would ultimately erupt into civil war, leading to an even more profound disruption of traditional order.

The Civil War Period: Temporal Authority in Crisis

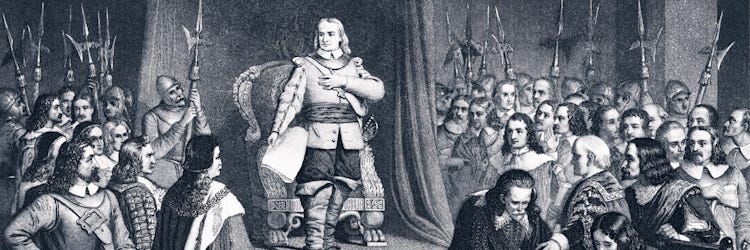

The English Civil War represents more than a political conflict between King and Parliament - it marks the violent collapse of an already-inverted social order and its replacement with an even more radical inversion. To understand this period through the lens of tradition, we must see how each aspect of the Four-Fold Order fell into greater dysfunction during this crisis.

The Civil War period saw not just political and military conflict, but the emergence of hundreds of religious sects, radical political movements, and new economic arrangements - all representing further departures from traditional order.

The breakdown manifested differently in each social order:

The Brahmin function fractured completely. The established Church of England, already compromised by royal control, split between royalist and parliamentary factions. More significantly, the period saw an explosion of Protestant sects - Puritans, Quakers, Ranters, Fifth Monarchists, and others - each claiming direct spiritual authority without traditional lineage or proper transmission. This represents what Guénon identifies as the proliferation of pseudo-spiritual movements that occurs when genuine spiritual authority is lost.

The Kshatriya function divided against itself. The nobility and gentry split between royalist and parliamentary causes, effectively negating their traditional role as a unifying warrior class maintaining social order. Many nobles found themselves fighting against other nobles, while merchants and yeomen farmers took on military leadership roles - a further confusion of proper social functions.

The Vaisya class emerged as perhaps the strongest beneficiary of this chaos. The London merchants, who had largely backed Parliament, gained unprecedented political influence. More importantly, new financial practices emerged during this period of uncertainty. The need to move and protect wealth during wartime accelerated the development of banking and credit systems that would later prove crucial to mercantile dominance.

The Sudra class suffered tremendously from both the direct effects of war and the breakdown of traditional social obligations and protections. The elimination of Christmas celebrations under Puritan rule provides a telling example of how common people lost access to traditional spiritual practices and festivities that had given meaning and rhythm to their lives.

Cromwell's regime represented a new type of inversion - rule by a military-mercantile alliance justified by pseudo-spiritual authority, an early version of what we would later call ‘neoconservatism.’ As Guénon explains, when legitimate spiritual and temporal authority are both lost, power tends to fall to those who control material resources. The Protectorate combined Puritan religious authority (a pseudo-Brahmin function), military dictatorship (a corrupted Kshatriya function), with mercantile interests (an elevated Vaisya function).

This arrangement prefigured aspects of modern governance, where military power serves commercial interests while various secular ideologies provide pseudo-spiritual justification.

During this period, people began to accept as natural and proper arrangements that deviated significantly from traditional order. The idea that religious authority should be subject to individual interpretation, that military power should serve commercial interests, and that social order should be based primarily on economic considerations - all these became increasingly normalized, to the extent that they are now taken as self-evident truths.

Moreover, the period saw the emergence of what Guénon terms "counter-tradition" - not merely the absence of tradition but its systematic inversion. The Puritan attempt to create a "New Jerusalem" based on their interpretation of scripture, while simultaneously destroying traditional religious practices and sacred sites, exemplifies this counter-traditional impulse.

The Restoration: Failed Attempt at Recovery

The Restoration of Charles II in 1660 might appear superficially as a return to traditional order, but viewed through the lens of sacred tradition, it represents something quite different - an attempt to restore traditional forms without their inner meaning or spiritual foundation. As Guénon explains, once genuine spiritual authority is lost, merely recreating its outward forms cannot restore its reality.

The restored monarchy found itself in an impossible position. Charles II attempted to re-establish traditional royal authority, but the very basis of that authority had been fundamentally altered. The king no longer ruled by divine right transmitted through proper spiritual channels (as in St. Dunstan's time), nor even by his father's claimed direct divine right. Instead, he ruled by Act of Parliament - his authority derived from the very merchants and gentry who had fought against his father.

The outer forms of traditional hierarchy were restored - monarchy, established church, aristocracy - but they now functioned primarily as shells containing very different realities:

- The Church of England resumed its position but remained subordinate to state power, making it incapable of providing genuine independent spiritual authority.

- The nobility regained their titles but increasingly functioned as a wealthy leisure class rather than a true warrior-leadership caste.

- The monarchy regained its throne but found itself increasingly dependent on Parliament for funding, and would eventually be reduced to a merely ceremonial position.

Most significantly, this period saw the continued rise of banking power and financial speculation. The goldsmiths' notes that emerged as a response to the instability of the Civil War period evolved into the beginnings of modern banking. This development represents exactly what Guénon describes as the final stage of materialism - the point at which even physical gold is replaced by pure abstraction.

Charles II himself accelerated this process through his relationship with bankers. The Stop of the Exchequer in 1672, when the Crown defaulted on its loans to goldsmith-bankers, paradoxically increased rather than decreased the power of financial interests. It demonstrated that even the restored monarchy was ultimately subject to financial constraints and credit worthiness.

The reign of James II represented the last serious attempt to restore something approaching traditional authority in England. His Catholicism, viewed in this light, represents not merely personal religious conviction but an attempt to reconnect with a form of spiritual authority independent of state power. However, this attempt failed precisely because the real power in society had shifted so dramatically. As Guénon points out, once society orients itself primarily toward material concerns, any attempt to reassert spiritual principles appears as an intolerable imposition.

The failure of the Restoration to truly restore traditional order stems from what Gurdjieff would call attempting to "make a clock from a matchbox" - trying to recreate something whole from parts that no longer contained their original essence.

The outer forms of traditional society were restored, but the inversion was clear. Spiritual authority remained subordinate to temporal power, while temporal power remained dependent on commercial interests. As a consequence, commercial interests increasingly dominated policy decisions, and the common people remained cut off from genuine spiritual tradition, leaving them as mere economic units in the system being constructed by the financiers and speculators.

Most importantly, the period saw the final establishment of usury as a normal and accepted practice. The foundation of the goldsmith-banker system on interest-bearing notes represents the triumph of what tradition had always recognized as a fundamental violation of natural law - the breeding of money from money itself.

The Final Inversion: The Glorious Revolution and Its Aftermath

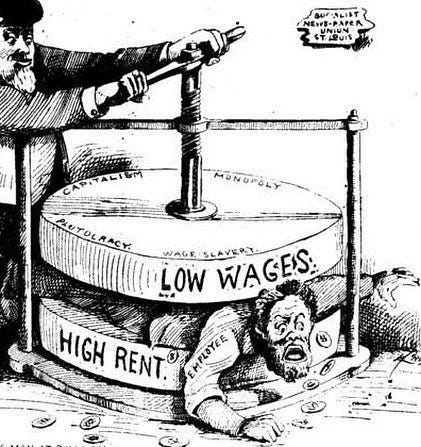

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 represents the final triumph of mercantile power over both spiritual and temporal authority in England. While often portrayed as a victory for religious tolerance and constitutional monarchy, from the perspective of traditional order it represents the complete inversion of natural hierarchy - what Guénon calls "the reign of quantity."

The ascension of William and Mary marked the first time English monarchs explicitly ruled by Parliamentary consent rather than divine right. Under the influence of St. Dunstan, kings ruled with authority delegated by the sacred order. Later this devolved into ‘divine right’. Now, the King ‘ruled’ with the permission of elected representatives who served banking and financial interests.

This wasn't merely a political change - it represented the final subordination of temporal power to commercial interests. The Declaration of Rights of 1689 was, in essence, a contract between the monarchy and the merchant-dominated Parliament. The king was now effectively an employee of the state and the bankers rather than its divinely appointed head.

The most significant development of this period was the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694. As Guénon explains, in traditional societies, money served merely as a medium of exchange subordinate to higher principles. The Bank of England represented something entirely new - the institutionalization of usury and the elevation of financial power above both spiritual and temporal authority.

The Bank was presented as serving the public good by financing government operations, but in reality it represented the final triumph of what traditional societies had always recognized as a perversion of natural law - the making of money from money itself.

The new arrangement completed the inversion of the Four-Fold Order:

Spiritual authority became completely subordinate to commercial interests.The Church of England functioned primarily as a guarantor of social stability, offering pseudo-spiritual legitimacy for the crimes of the regime and the exploits of the bankers. Genuine esoteric knowledge was largely lost or driven underground

The monarchy became ceremonial rather than genuine temporal authority, and the nobility increasingly functioned as a wealthy leisure class. Military power served commercial rather than traditional aims.

Merchants and bankers became the true ruling class. Money and banking became the primary source of social power.

Common people became purely economic units. Traditional social protections were entirely replaced by market relations. Spiritual life was reduced to empty forms or emotional enthusiasm.

This inversion was particularly insidious because it maintained many traditional forms while completely inverting their meaning.

The aftermath of the Glorious Revolution saw the rapid expansion of British commercial and imperial power. This expansion was by purely commercial considerations. The East India Company's domination of India provides a perfect example - a commercial enterprise wielding political and military power in service of profit rather than any higher principle.

This period also saw the emergence of what Gurdjieff terms "American fever" - the endless pursuit of material improvement and innovation without regard for traditional wisdom or spiritual development. The scientific and industrial revolutions that followed would accelerate these tendencies, creating the thoroughly materialistic modern world

Conclusion: Understanding Our Current Crisis

The transformation of English society from the time of Henry VIII through the Glorious Revolution provides us with a clear template for understanding how traditional order breaks down and inverts. This wasn't merely a political or economic transformation, but a complete inversion of the natural hierarchy that traditional societies understood as necessary for both social harmony and human spiritual development.

At each stage, the process followed a clear pattern:

1. The subordination of spiritual authority to temporal power

2. The corruption of temporal power through this usurpation

3. The rise of commercial interests to fill the resulting vacuum

4. The final triumph of purely material considerations over all higher principles

This pattern, as Guénon explains, represents not random decay but a systematic inversion of traditional order. Each stage prepared the way for the next, continuing the worsening of what Gurdjieff called the “abormal being conditions” exacerbated by the rule of a predator class of “power-possessing beings.”

This process, which is today called “Progressivism”, is the political manifestation of the rejection of ‘genuine Being duty’, resulting in a social order arranged to serve the base desires of a parasitic financial elite.

The implications for understanding our current civilizational crisis are profound:

First, we can see that our modern arrangement isn't natural or inevitable, but the result of specific historical inversions of proper order. The dominance of financial interests over all other considerations, which seems normal to modern people, represents a complete inversion of traditional hierarchy.

Second, we can understand why attempts to "reform" the system while maintaining its basic inversions are doomed to failure. As Gurdjieff explains, once wrong crystallization occurs, mere adjustments cannot restore proper function - a complete "re-crystallization" based on proper principles would be necessary.

Third, we can recognize the pattern of pseudo-restoration that maintains outer forms while inverting inner meanings. Much of what passes for "tradition" in modern society represents this type of empty formalism, which Guénon identifies as characteristic of the final stages of cyclic degeneration

Most importantly, this analysis helps us understand why modern civilization, despite its material achievements, fails to provide conditions conducive to genuine human development. The Four-Fold Social Order wasn't merely a political arrangement - it was designed to facilitate the transformation of human consciousness and being. Its inversion necessarily produces a society oriented toward purely material aims.

This understanding has particular relevance for those interested in Gurdjieff's ideas about human spiritual evolution. The conditions he described as necessary for genuine inner work - including proper influences and guidance - were traditionally maintained by the correct arrangement of society. Their absence in modern society isn't accidental but the direct result of specific historical inversions.

For those seeking to understand our current predicament, this history provides essential insights. We live under a regime where:

- Financial considerations dominate all aspects of life.

- Various counter-initiatory substitutes have replaced genuine spiritual authority.

- Spiritual counterfeits are used to promote, rather than check, the degeneration of good being habits.

- Traditional forms persist but without their inner meaning.

- Material progress occurs at the expense of human development.

Yet understanding this process of inversion also provides keys for those seeking to work against it. As Gurdjieff taught, genuine transformation requires understanding the laws that govern both individual and social development. He writes that hope lies in those who begin to understand "the terror of the situation" and strive to transform themselves, stating that such individuals might "become capable of penetrating into the essence of all kinds of truths" and "at last learn the genuine truth about everything existing."

The restoration of spiritual authority begins here, not with the effort to revive forms and structures that no longer have any vitality or potency. As individuals strive to develop themselves, then there is a possibility to organize, influence, and form a spiritual critical mass as demonstrated by St. Dunstan and Ashiata Shiemash.

The example of St. Dunstan reminds us that proper order can be established even in difficult conditions, provided there is access to genuine spiritual authority and understanding. While we cannot simply turn back the clock, through what Gurdjieff calls “conscious labor and intentional suffering,” we can work to understand and align ourselves with the principles that traditional order served to maintain.